Hayden Pedigo’s “Long Pond Lily”

"She came to me with two day lilies which she put in a sort of childlike way into my hand & said ‘These are my introduction’ in a soft frightened breathless child-like voice—& added under her breath Forgive me if I am frightened; I never see strangers & hardly know what I say." So recounts a contemporary of Emily Dickinson upon first meeting the poet. What did Dickinson hope her new acquaintance would see in that eccentric gift? What did she see in it herself?

Hayden Pedigo elicits similar questions with his instrumental guitar piece, “Long Pond Lily,” only in a more immersive manner. Instead of dropping flowers in our hands, he drops us into slow-moving water. A spritely melodic figure announces the star-like spray of petals opening before us, and we wade with the floating flower, listening. But listening for what?

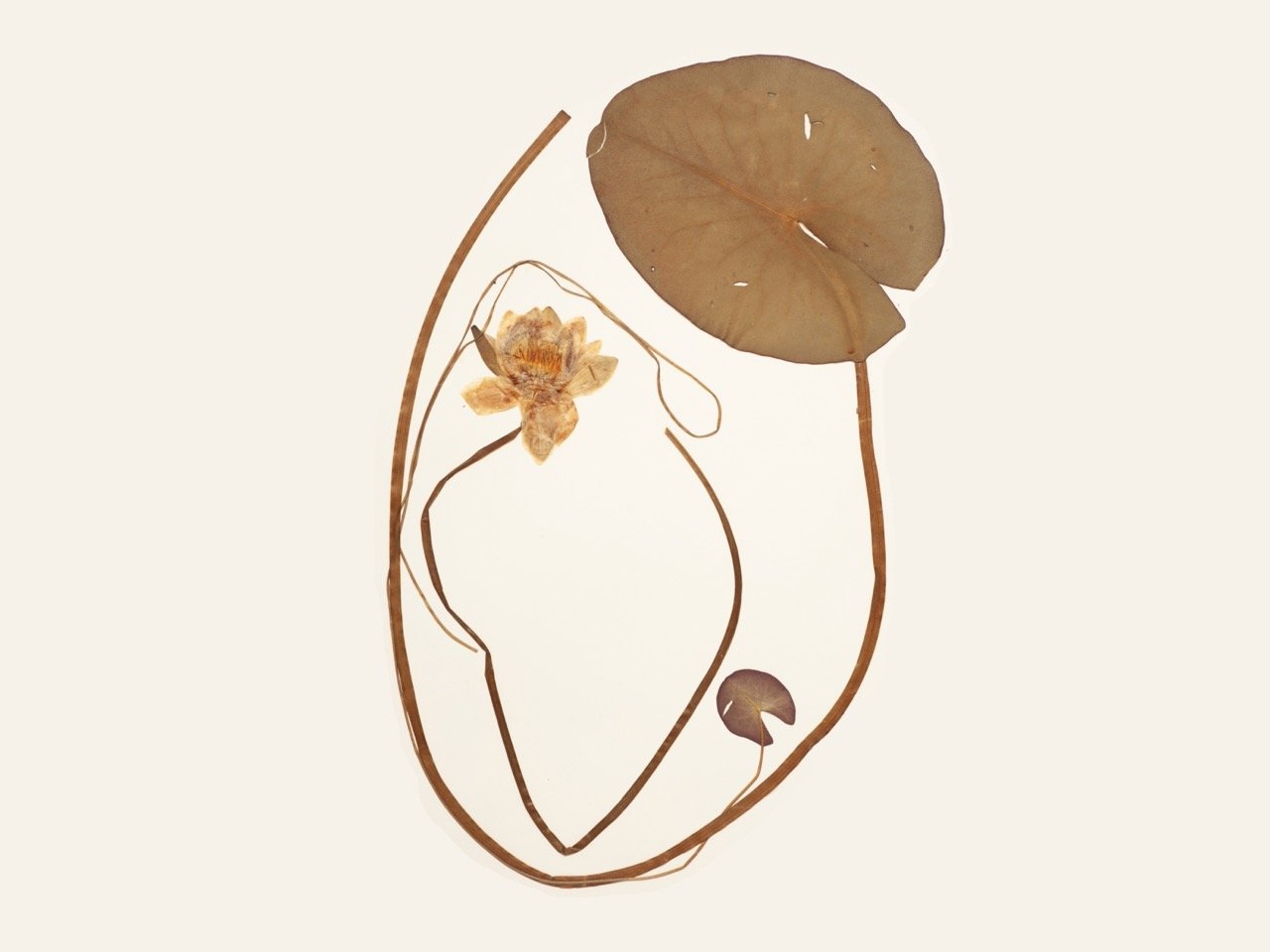

A pond lily

Everything we need for an answer exists, sonically, in the song’s opening. We have the melodic theme, picked out on the high strings of an acoustic guitar to trace the contour of the lily’s whorl. Beneath that, Pedigo thumb-picks deep de-tuned notes from the guitar’s lower register. Monet once said of his lifelong project of painting water lilies: “I have again begun on things that are impossible to do: water with waterweed undulating on the bottom..." This is what these lower notes do: evoking the lily’s rhizomatic roots swaying below the surface of the water, they undulate. Heard most clearly through a good pair of headphones, Pedigo’s bass notes roll and ripple thanks to a guitar rich in overtones, and a guitarist’s decision to tune his instrument just so to exploit, with richly resonating open strings, the shimmering weave of those overtones.

Known for exploring a variety of idiosyncratic guitar tunings, for “Long Pond Lily” Pedigo has chosen the Open C tuning most famously associated with primitive guitar legend John Fahey and, in particular, Fahey’s “Sunflower River Blues” (note the water-flower connection). An open tuning is one that conforms the guitar’s open strings to the notes of a chord. If a composer tunes to a chord and chooses to write in the key of said chord, many opportunities arise for cross-resonances: the guitarist frets a c here, and any of the open strings around the fretted note might vibrate in acoustical sympathy. Further, on guitars built from particular woods, open strings will offer a rich mélange of overtones, which are additional frequencies emanating from the fundamental pitch. These spectral higher frequencies give notes their particular texture, and a warbling, buzzing, swelling open string’s texture is especially thick with them. A low open c string like the one Pedigo deploys at the opening and throughout “Long Pond Lily” emits, in a sonic cloud around that fundamental c, a series of higher, fainter notes: C, G, E, B♭. The tension between the guitarist’s steady thumping rhythm and that cloud of overtones creates our waterweed undulation—and points forward to elements that will develop throughout the tune.

“Long Pond Lily” features three distinct sections followed by the return, with alteration, of Sections One and Two. Section One, in its first form, gives us the previously mentioned undulation, thumbed in a stately-paced common time (two or four quarter notes per measure), and atop that the lily-figure unfurled in quick hammered triplets. The harmonic content involves a movement from C Major to F Major, with the F Major weakened by the chord’s seventh note, e, ringing out from the guitar’s topmost string. Section Two introduces a bouncier common time foundation. Harmonically, this section strays a bit further from a pure C Major feel, particularly through the use of a B♭ chord. In the upper register, an electric guitar enters, adding a more relentless repetitive triplet figure. The electric triplets prefigure something and, in their intensity, push toward it: The major rhythmic shift of the piece, Section Three’s move from common time to triple time (three quarter notes per measure, e.g. a waltz or a minuet). The three-note nature of the first two sections’ upper register, formerly set in contrast to the two- and four-note structure of the song’s lower register, has now effectively transformed the lower register in its own tripart image. C Major remains the tonal center, but F Major becomes more prominent, with B♭ Major and A♭ Major chords confirming that we’re in harmonic territory distinct from where we began. The melodic figures of both acoustic and electric guitar are now blended into one. Here, pond and lily unify, and we with them, and the song reaches its harmonic and textural climax—before sighing back into its first section. Section One, however, returns with something new: a melancholic sheen, delivered by swelling synthesizer, that continues till the end of the song. The synthesizer, in a string- or pedal steel-like wash, makes explicit what was present in the low undulating drone at the start of the piece. It teases out those upper phantom tones, while adding in some of the more alien pitches from Section Three. After the third section’s peaking of development, the final reiterations of Sections One and Two mark a dying away. The high lead guitar’s fast triplets conform to a simpler figure. In its final moments, the song decays into repose.

Hayden Pedigo performing at Avondale Upstairs in Birmingham, Alabama.

And there we are, still wading, while the flower sags, withers, dissolves around us. Each moment of the song has prefigured the next until prefiguring becomes the song’s disfigurement. Like Emily Dickinson, Hayden Pedigo has given us a blooming thing seeded with un-blooming. But why? Toward the end of her life, Dickinson wrote to a friend: "...the only Commandment I ever obeyed—’Consider the lilies.'" On its face, Dickinson’s comment references Matthew 6:28: “And why take ye thought for raiment? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin.” In other words: Trust in Providence as a flower does and all will be provided. But Dickinson’s body of work, ever ironical, ever death-minded, suggests a different reading: Lilies, as perennials, continuously cycle through life, death, and rebirth, with the germ of each in each. That cycle is what Dickinson, breathless and child-like, dropped in her new acquaintance’s hands. Likewise, Pedigo plunges us in the pond and reels the lily round its life with ours reeling, breathless and child-like, after it.

By Charles Conway

Charles is an aspiring writer who grew up in Slapout, Alabama, and studied Music and Philosophy at the University of Montevallo.